Introduction

Then in 2017 came along the Fourth Money Laundering Directive, which resulted in the much tighter 2017 Regulations.

It was around this time that the LSAG (Legal Sector Affinity Group) was set up. LSAG is a Group made up of the Law Society and other professional body supervisors named in the Regulations. They get together to interpret the Money Laundering Regulations for the legal professions and provide guidance.

Whereas before, we had the Law Society’s money laundering practice notes to rely on, we now have the LSAG guidance, which directly replaces the practice note. It is your first port of call for all money laundering guidance. This latest version of the guidance, which was published in January this year, is still in draft format pending approval from the Treasury.

So in a nutshell this document is as close as we get to a definitive guide to the Money Laundering Regulations 2017. Which means that it is important that we are familiar with what it says and requires of us.

Why should we care about the LSAG guidance?

I think there are a couple of major reasons all solicitors should sit up and take note.

The first is that AML compliance is a professional duty. Our regulator, the SRA, has in the past couple of years set up a dedicated Anti-money Laundering supervision department, whose sole job it is to check that firms are complying with the Money Laundering Regulations. That department is well resourced and very active. You have probably seen reports in the legal press about the SRA doing sweeps of the profession and spot checks. Quite a few of our client firms have been on the receiving end of an AML review out of the blue..

And this team at the SRA is becoming increasingly proactive. They know what they are looking for and are targeting specific themes of compliance. One of the first things they started looking at was whether firms had in place effective firm-wide risk assessments. They are now moving on to add other elements of compliance. Given that the SRA has very broad powers to take enforcement action and generally make your life difficult, this is probably the most urgent reason to take the LSAG guidance seriously.

The second reason is that the AML regime itself, made up of the Proceeds of Crime Act, Terrorism Act and Money Laundering Regulations, contain criminal offences which can catch out solicitors. In short, you do not have to be knowingly helping a money launderer to be guilty of an offence – it could be as simple as not having the correct processes and controls in place.

Now the fear of criminal penalties has traditionally been the stick with which lawyers have been beaten into compliance. Ever since money laundering training became widespread after 2002, there is always a slide on 15 year sentences for the primary offences. But I think most solicitors have gotten comfortable with that risk over time, and many take the view that so long as they are vigilant and trying to do the right thing, criminal penalties are unlikely to be a problem. For the most part that is correct, although it is worth remembering that solicitors have been imprisoned for money laundering offences.

The biggest area of regulatory risk for law firms is undoubtedly the administrative aspects of the Regulations. Risk assessments, due diligence, policies reporting, training and so on – it’s very easy to get these things wrong and unintentionally become vulnerable to sanction. I think this is specifically true right now. In my experience, most firms did a pretty good job of AML compliance under the 2007 Regulations.

But unfortunately, I have seen a worrying lack of engagement with the 2017 Regulations. There are large swathes of the profession that assumes that if they were compliant under the old regulations then they would be okay now. That is emphatically not the case. The 2017 regulations brought in some significant changes and if you haven’t been paying attention, the LSAG guidance is your opportunity to catch up.

So that’s why it’s important. Now the bad news. As a practical guidance document, this guidance leaves a lot to be desired. It has been almost completely rewritten since the previous version, and certainly feels like it has been drafted by committee. It weighs in at over 200 pages and 5 hours reading time, according to the Law Society website. That’s just the tip of the iceberg of course – the action points that come out of the guidance could be significant, depending on what steps your firm has taken towards compliance with the 2017 regulations already.

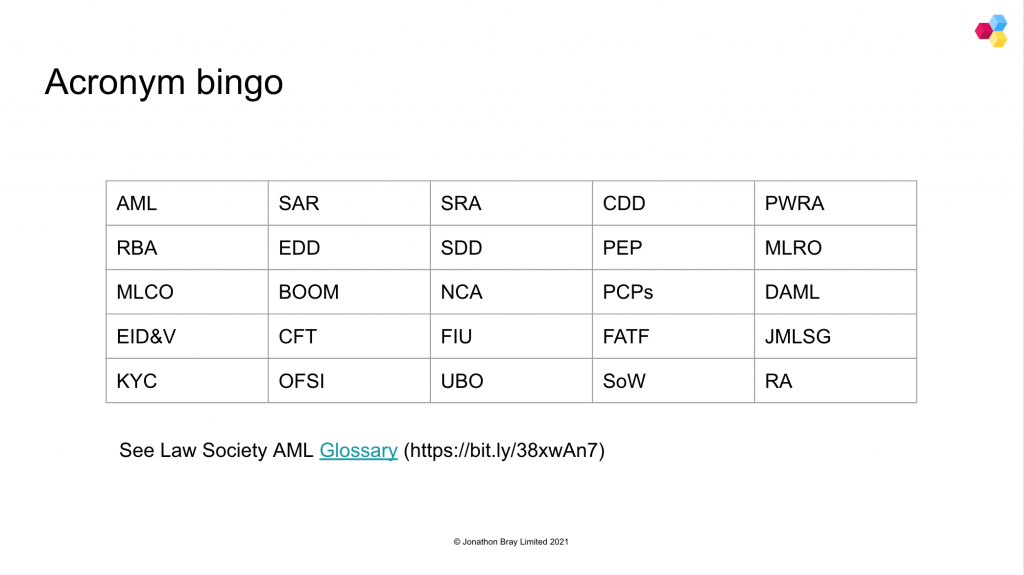

Acronym bingo

I was on one of the Law Society’s AML webinars recently, where the presenters used every acronym in the book without ever explaining what they meant. There was an expectation that everyone knew what they were on about, and it became very clear from the snarky chat comments that this was anything but the case!

But if you are going to get along with AML compliance I am afraid there is no getting away from these terms. So I’ve found it’s best to accept and embrace them – otherwise you will just get lost in regulator speak. Usefully, the Law Society has published an online glossary. I was going to count all the abbreviations, but I only got down to C in the list and was already up to 30! So yes, there are a lot.

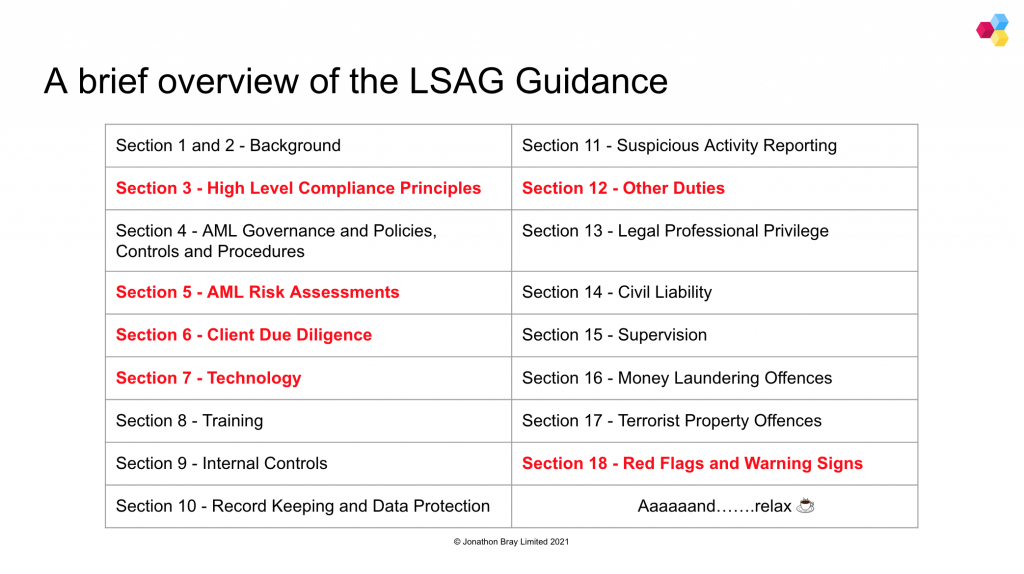

A brief overview of the LSAG Guidance

So what does 200 pages of acronym-heavy anti-money laundering guidance include? In this table you will see all 18 sections.

Now don’t worry, I am not going to go through and summarise each chapter. We would be here forever. But there are a few I would like to draw your attention to.

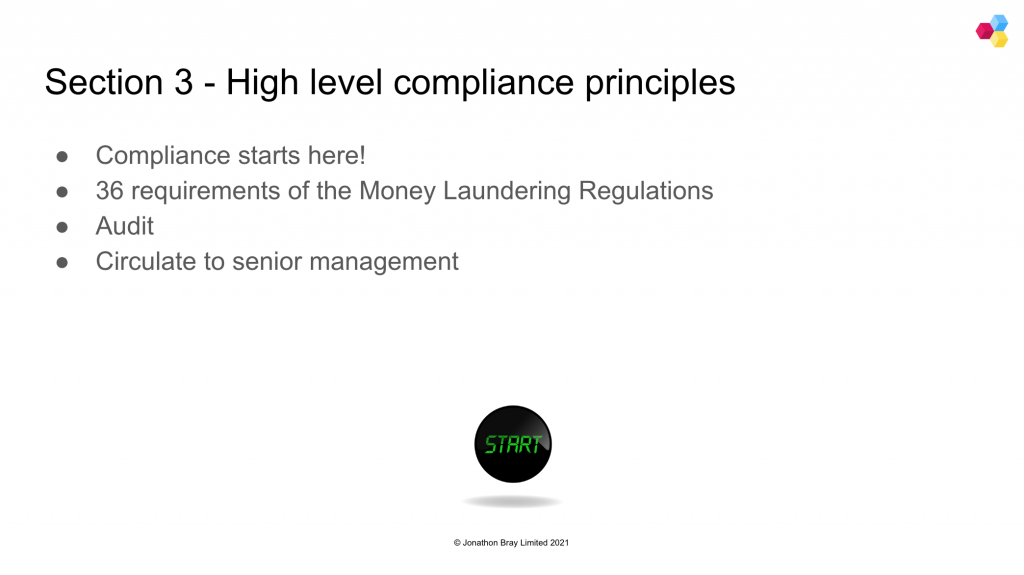

Section 3 – High level compliance principles

The first section I’ve highlighted is Section 3 – High level compliance principles. This is something that was missing from the previous incarnation of the guidance, but which is incredibly helpful. And at just 3 pages long, it is also an easy one to start with. Essentially, what this section does is to set out all of the requirements of the Money Laundering Regulations as they apply to law firms. There are 36 high level requirements, and it is these requirements which the guidance then goes on to expand upon in the rest of the document. So, it’s a useful place to put all of the guidance into context.

It would also make a useful audit tool. In fact, it’s what we now use to audit firms’ AML compliance. We’ll circle back to this later, but suffice it to say that there is a now a hard requirement to obtain an independent audit of your firm’s compliance processes. That’s something that until recently has gone very much under the radar.

I think if I were an MLRO I would also extract this part of the guidance and send it round to the business owners, partners, directors or senior management team to remind them of everything that AML compliance involves.

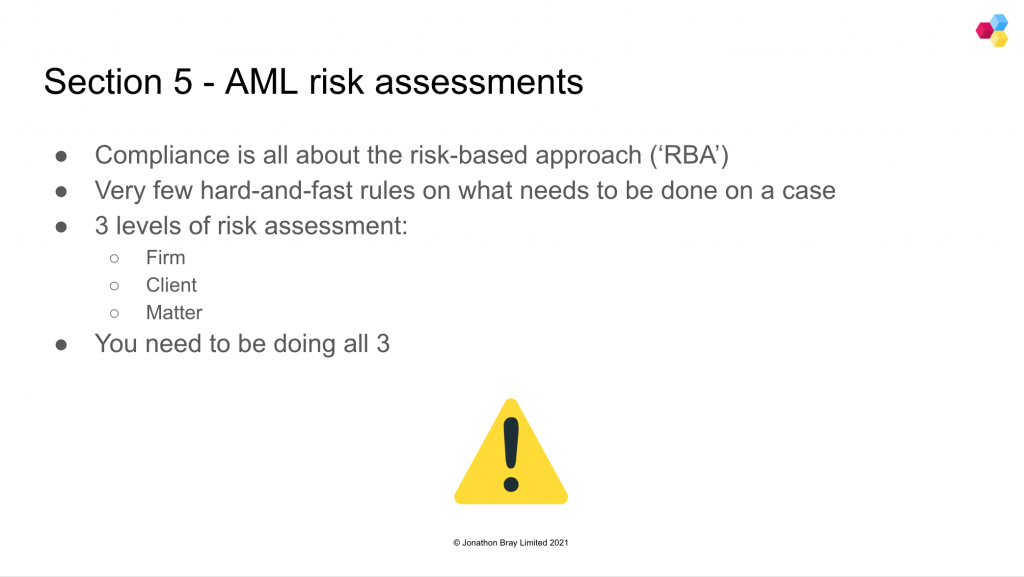

Section 5 – AML risk assessments

The next section that I think is particularly important is section 5, AML risk assessments. You might have heard the phrase ‘risk based approach’ before. That, in essence, is how the legislators intend us to tackle financial crime. It means not having a tick box approach to compliance, but instead looking at the client or transaction in front of you and thinking, “How far do I need to go to understand the identity of this client or its beneficial owners. Are there any factors that increase or decrease the risk associated? Do I truly understand what I am being asked to do, and does it make sense in the context of what I know about the client?”

OK, that is overly simplistic, but if you had to sum up what questions the compliant solicitor would be asking themselves, it wouldn’t be far off. So everything about the ‘risk based approach’ is subjective, and relies on your professional judgement and understanding. That’s why there are very few black-and-white answers to questions like “What ID documents do I have to get for this client? How far up the corporate tree do I need to go? How far do I need to go to establish source of funds?” The answers to those questions inevitably start with “It depends”. It depends on the money laundering risk presented by this particular client and their particular legal matter, and your particular firm’s systems and controls.

And that’s where risk assessment comes into play. It is the part of the puzzle where you establish what the risks are so that you can discharge your duties accordingly. It is an essential piece of the compliance jigsaw, and traditionally law firms have not been very good at it. I think we naturally tend to prefer having someone tell us what to look for. That is easier, quicker and means we can get straight on with doing the lawyering. But that tick box mentality is precisely what the regulators are trying hard to beat out of us. And why AML compliance is ultimately so hard.

So let’s step back a bit. Under the Regulations there are three levels of risk assessment: the firm level, the client level and the matter level. You need to do all three. This is not negotiable. Let’s look at all three types of risk assessment.

The first is the firm-wide risk assessment, or practice-wide risk assessment as it is called in the guidance. This is a central document that every firm subject to the money laundering regulations must have in place. It is described as the cornerstone of AML compliance, such is its importance. If you don’t have one of these in place, or if you have not gone through the exercise properly, you will not pass any SRA inspection.

So what is a firm-wide risk assessment? It is essentially a high level analysis of the firm, it’s practice areas, client base, systems and controls and other important factors. Essentially, you are looking for the vulnerabilities – what would a money launderer look to exploit in your firm? Would it be the fact that you are experts in cross border cases, or specialise in property, rarely meet your clients, or have weak due diligence systems in place? Every firm is different and every firm-wide risk assessment should be unique. The SRA is actually quite critical of firms when they spot templates being used without amendment.

Out of this analysis comes a document which has to be signed off by senior management. And then comes the most important bit: the risk assessment is supposed to inform how the firm approaches compliance with the rest of the money laundering regulations. Everything from policies and training through to the technology used and the records that kept. They all flow from that central document.

Which also means that the firm-wide risk assessment is a living beast. You are supposed to update it whenever there is a material change to your practice – let’s say you open a new office or department – or when there is a change in the underlying regulations and guidance.

The second and third levels of risk assessment (client and matter) are closely linked, but are not the same.

A client risk assessment will usually take place when you first take on a new client. This is the bit where you look at the client’s risk factors such as where they are based, whether they are a Politically Exposed Person, (in the case of a corporate client) their ownership structure and so on. There is a whole list of things to be considered as part of this process and the LSAG guidance goes into this in quite some detail.

This is different to a matter risk assessment, which usually happens when you are instructed on a new matter by a client. You will be looking at risk factors such as whether the matter is consistent with your knowledge of the client, where the parties are based, what areas of law the matter involves and so on. Again, the guidance is helpful in setting out what exactly a matter risk assessment should look like.

Note that you should be doing a matter risk assessment for each new piece of work taken on, even for existing clients. And where you take on a new client, for their first instruction you will end up with two separate but overlapping risk assessments: the client and matter. And yes, that is a lot of paperwork, but don’t shoot the messenger.

Section 6 – client due diligence

That then moves onto section 6, client due diligence or CDD. Now, you will be glad to know that nothing much has changed over the last 3 years regarding CDD, so if you had already taken steps to get compliant with the 2017 Regulations you should be okay still. Those lovely terms like Enhanced due diligence, Simplified due diligence and ongoing monitoring are still there hanging on. So too are the rules around beneficial ownership and control. Not easy stuff, but not exactly new.

I just wanted to draw your attention to the new bit of guidance in this section around source of wealth and source of funds. This is something that causes a great deal of confusion and hand wringing at most property and transactional firms.

Source of funds and source of wealth are two different things. From experience, most firms concentrate on the source of funds, or the “where is this money coming from, and how did they get it?”, question. So the solicitor will typically check that the funds are coming from the client, rather than a third party. They will consider whether it’s reasonable that the client has this money at their disposal, so might for example want to see evidence of a person’s entitlement to an inheritance or a loan. Sometimes the solicitor will take comfort from the fact that funds are coming from a UK bank, although that has been debunked by the guidance as being even remotely equivalent to safe money. UK banks are not necessarily safe.

Arguably the more important questions stem from source of wealth i.e. “does my knowledge of the client fit with how they are telling me they arrived at this level of wealth?” In the case of a simple conveyancing transaction, for example, that means going beyond asking how a buyer is funding the deposit, to considering whether it is reasonable that a buyer living in a bedsit is investing in an upmarket London address. More investigation might be needed if it becomes apparent that the client is borrowing money from a third party. For a corporate client you might be asking to see P&L statements or balance sheets, perhaps even agreements which entitle them to certain payments.

Source of wealth goes to the heart of what you understand about the client’s financial situation, and is therefore much more informative, whereas source of funds is more about limiting the investigation to the flow of money itself. It’s an important distinction to get right.

Section 7 – Technology

Section 7 is brand new guidance which focuses on technology and how that impacts upon AML compliance. This is quite significant because for the first time we have this official recognition that paper-based ID checking is perhaps not the best way forward. It has always amazed me the number of times I have seen firms accept photocopies of documents on face value, without stopping to think whether they might have been forged (it costs a couple of pounds to download a fake utility bill if you know where to look) or whether the person in front of them is actually the person in the picture.

Over the years, so-called RegTech has improved a lot. What started off as simple database checkers now incorporate biometrics and artificial intelligence. If you’ve not seen these in practice before, I would urge you to have a look, they are quite something.

But the guidance cautions us to not rely too heavily on these technologies – they should never take away the critical thinking skills needed to spot red flags and warning signs. They are useful and efficient tools for ID verification, but that is only one piece of the puzzle. Technology will never tell you if the transaction makes sense knowing what you do about the client, or if something is just slightly fishy. A big green tick in the ID verification system does not mean that you have done everything that you need to.

The guidance also says that we have to properly understand the technology itself. We cannot just buy a system off the shelf, accept the salesman’s assurances about compliance, and assume it does the job. The onus is very much on the law firm to check the credentials of the technology provider and to take steps to understand, as much as possible, how the system works and which data sources are being interrogated. Which of course makes sense, although I do feel for some firms who may not feel equipped to make those assessments.

Other issues highlighted in this section include Training (i.e. any system is only as good as the end user who inputs data and interprets the results) and a reminder about Screening relevant employees under the Regulations. It’s something that is often missed, and these e-verification systems could be a suitable tool to quickly comply with that part of the rules.

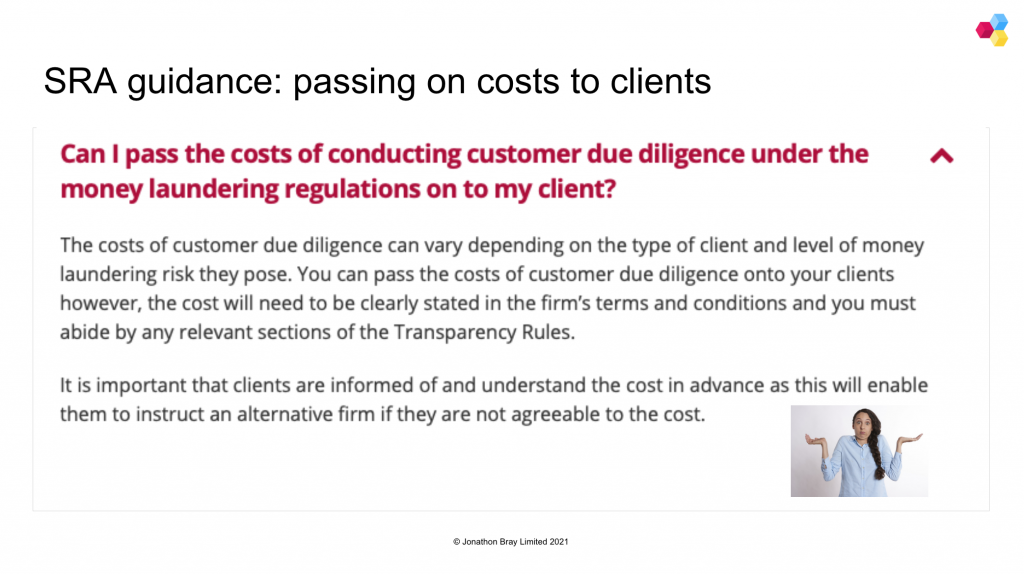

SRA guidance: passing the cost on to clients

Just a quick word too about passing on costs of e-verification systems to the client. Until recently, it was the case that the SRA saw ID verification as an overhead which should not be passed on to the client, certainly not as a disbursement, although they reluctantly agreed that nobody could stop solicitors charging time costs for undertaking the check. Although ironically, that would usually end up costing the client more.

The position seemed to have changed in a bit of SRA guidance that disappeared almost as quickly as it appeared. It was pretty clear in saying that passing the cost of ID verification is acceptable, subject to the Transparency Rules and costs information. I don’t know why this has been removed – perhaps they just don’t want to encourage firms passing on overheads. Your guess is as good as mine. [Update: the guidance has since reappeared on the SRA website].

Section 12 – Other duties

Anyway, back to the LSAG guidance. Section 12 deals with ‘Other duties’. This includes the new trust registration regime, which is beyond the scope of this session, but will be particularly relevant to firms that act as professional trustees. Also relevant for financial crime fighters is the new Companies House discrepancy reporting obligations. Essentially, if your client is a company or LLP then you have to get evidence of their registration. Where you come across a discrepancy between the official register and what you know about the client, you have a duty to report that directly to Companies House, unless to do so would breach professional privilege.

Section 18 – Red flags and warning signs

And last but very much not least, I have picked out Section 18 as being incredibly important. In fact, of all the sections we have been through, I would have to say that this is probably the most important, because it actually sets out practical examples of situations where you need to be on heightened alert.

It covers situations relating to the client and parties to a transaction, the source of funds, the nature of the transaction, as well as practice specific warning signs in private client work, property, litigation etc.

Of all the AML training sessions I have ever given or attended, far and away the most valuable bit is usually the group discussions around money laundering scenarios and practical examples. If I were an MLRO I would definitely be directly all staff to this section of the guidance and testing them on it. Can they pick out the red flags in some fictional scenarios? Have you got any horror stories or near misses you can share with the rest of the firm? It often works well to send out a firm-wide pat on the back to the person who spotted a red flag and escalated it to the MLRO, whether or not it resulted in any reports being made to the authorities.

Definitely use Section 18 to your advantage.

Okay, so that’s a brief spin through the guidance document itself. You’ll note that we haven’t touched upon some of the key aspects of AML compliance, including policies, reporting and record keeping, all we have done today is pick out some of the major changes. The rest stays pretty much the same.

Things that jump out

Next, I just want to spend a little time on some observations on the guidance document itself. I don’t want it to come across as overly critical because the drafters have clearly tried to make it as useful as possible, and frankly I couldn’t have done any better. But I do think it is worth pointing out a few issues with the document.

Firstly, the guidance has adopted a new approach where they label all requirements as either ‘Must, Should or May’. ‘Must’ means anything that is a direct requirement from legislation. ‘Should’ means anything that the SRA would expect of you, and you would have to have good reason for departing from. ‘May’ is a suggestion and good practice advice.

This was a really promising way to categorise and prioritise the guidance. Unfortunately it falls short because there is no ‘at a glance’ way to see which parts of the document are hard-and-fast rules and which are merely nice to have. Instead, all of the musts, shoulds and mays are buried in the heavy text so are not much use at all. Even a bit of colour coding would have helped. Perhaps they will sort that out in a future update.

The other thing that hits you straight away is that this feels very much like a draft document. It is wordy, there are spelling mistakes and it all feels a bit rushed. It’s certainly not as polished as the old Law Society Practice Note on AML. I wouldn’t be surprised if the Treasury recommends some amendments before approval.

But more fundamentally, this is a document that comes across as being written by money laundering professionals for money laundering professionals. In my view they have completely missed the opportunity talk directly to the people the guidance is intended to help, i.e. time-poor law firm owners who are not steeped in money laundering regulation day in day out. And there is this an underlying unrealistic assumption about the amount of time and resources that law firms have available to deal with all this stuff.

I’m sure the counter argument would be, “that’s irrelevant, the rules are what they are” and I do have some sympathy with that. It just would have been nice to see some acknowledgement of the commercial realities of running a law firm. Instead of a practical guide to AML, what we have ended up with is what feels like a regulator’s handbook.

My worry is that at some point AML compliance is going to become unsustainable. In just a couple of decades we have gone from almost zero compliance requirements to having to shop your client if their Companies House filings aren’t correct. And you just know that one in place, none of these requirements are likely to go away.

I’ll let you into a little secret. I recently drafted a client and matter risk assessment for a client. I purposely did it in line with the 2017 Regulations and the LSAG guidance, making sure I hit everything you are supposed to consider when taking on new work. Bearing in mind this was for general conveyancing and trusts work, meant for every new client taken on by the firm, can you guess how many pages it turns out to be? 32! 32 pages! Nobody is ever going to fill that in properly so you have end up having to prioritise certain parts of the risk assessment.

Another general point is the irony of having so much AML regulation and associated guidance that it ends up forcing you into having to take more of a tick box approach. Otherwise, how are you ever supposed to remember every single thing you are supposed to be doing as part of the compliance process? I think we might find more firms reverting to checklists and tickboxes just to cover themselves, even though that is against the spirit of the entire AML regime.

And the last thing that jumped out to me upon reading these 200 pages of guidance was the emphasis placed on the firm-wide risk assessment. It is seen by our regulators as the cornerstone of compliance, and everything else, your policies, procedures, due diligence, training, retention, all flows from this one document. It just so happens that it’s probably also the easiest thing for the regulators to check up on – it would be much harder to do a substantive review of firm’s compliance in practice. That’s why, if you take one thing away from this session, it is to revisit your firm-wide risk assessment, and if you don’t yet have one, that should be an urgent priority!

What you need to do

So what else should you be focusing on in response to the LSAG guidance? I think there are a few things.

If you are the MLRO or COLP you should pick out the bits of the guidance document that are relevant to your firm and spread the word that the SRA is watching and you are expecting to have to answer to them over the next year. We’ve already mentioned the firm-wide risk assessment but it’s worth underlining the point that this is an essential process to go through, not just for compliance but also to demonstrate compliance.

I mentioned it briefly earlier, but the independent audit requirement under Regulation 21 is something that has gone under the radar somewhat. Just to summarise, most law firms are required by law to commission an independent audit of their firm’s AML systems to check everything required by the regulations is covered and that the systems are working as they should. This audit can be conducted internally, but the auditor has to be somebody who is not involved in putting together the systems, to avoid people marking their own homework. The other option of course is to outsource the audit, and that’s something we would happily help with.

It’s a good time to check your registrations with the SRA. All firms subject to the Money Laundering Regulations have to be registered and authorised for that activity by the SRA. There are also a couple of strange additional registration requirements that some firms miss. One of them is the registration of all beneficial owner, officers and managers, which some smart Alec decided to abbreviate as BOOM. That means every time a partner or director joins the firm there is a registration requirement. You can do this through mySRA and there’s lots of guidance on the SRA site, but just so you are aware, they will need to get a DBS check as part of the notification.

I’ve also mentioned TCSP status on the slide. TCSP stands for Trust an Company Services Provider and it covers things like being a professional trustee, setting up companies and trusts, providing a registered address for client among other things. There’s nothing stopping you doing these things but technically it does not fall under the SRA’s remit and you have to be registered with HMRC as a TCSP. You can, confusingly, apply to be on the HMRC register through the SRA. And if any of that makes any sense to you, I’m amazed. But it is worth checking that your registrations are in order.

The last item on this slide is there to remind you not to lose sight of the big picture. Yes, there are some important things you have to do to comply with the Money Laundering Regulations, and they are compulsory, but they do represent the administrative side of the money laundering regime.

The purpose of the AML regime in the first place is to stop criminals from using your firm to clean the proceeds of drug trafficking, forced prostiution, and people smuggling. Nasty, nasty stuff. And the best weapon in your armoury is your professional judgement and vigilance. If something doesn’t feel right, take further action. Trust your gut, that’s so important. And make sure that message reaches everyone on the front line, because they truly are your crime-fighting superheroes.

The missing piece of the pie: ‘Tax advisers’

Just very quickly, a huge omission from the LSAG guidance is the issue of tax advice. To be fair to them the SRA has done a lot of work around this lately, and we have been doing our bit through blogs and LinkedIn to try and raise awareness.

But to sum it up, the issue is this: tax advisers are caught by the Money Laundering Regulations. Traditionally, the definition of tax adviser was pretty narrow and didn’t really affect lawyers.

But that has all changed.

Under the 5th Money Laundering Directive, the definition of tax adviser has been significantly broadened to include any advice or material assistance with tax matters. So potentially, there are practice areas that are now caught by the Money Laundering Regulations for the first time, which brings in all the AML compliance with it. The examples I can think of include settlement agreements in employment departments, will writing, high value personal injury, and potentially matrimonial cases.

In all these cases it’s likely you are going to be duty bound to advise on tax, even in a very general manner, which is likely to get caught by the new definition.

Unhelpfully, there is yet to be any proper guidance on what this means. We are left in the position where firms have to make up their own mind whether they are now counted as being tax advisers for the purposes of the Regulations.

I think there are a couple of major implications for this: there will be some firms who have never been authorised by the SRA for money laundering activities. Because they never needed to be because their practice areas sat outside of the regulations. That may now have changed, meaning that they will have to seek SRA registration for the first time. It’s a simple process but easily missed.

The other implication is that some departments may get sucked into money laundering compliance. Those teams are going to have to be trained and coached in the ways of AML risk assessment, due diligence etc – in just the same way that property lawyers are.

That is a pretty big challenge.

![The Legal Sector Affinity Group (LSAG) Guidance 2021 – What solicitors need to know [Long read] The Legal Sector Affinity Group (LSAG) Guidance 2021 – What solicitors need to know [Long read]](https://www.jonathonbray.com/wp-content/uploads/bfi_thumb/dummy-transparent-obadi0wivgww4ihdae9xs8qbf69cenia3a5vcdxo0e.png)