Law firm IT projects are notoriously difficult to get right. We have all known law firms that have spent big on shiny new case management systems, only to find that it has little real world benefit. Or people just don’t use it in a way that realises the theoretical gains.

We spoke to Alex Hutchinson, the freelance IT director, to find out why law firm IT projects often fall down.

Hi, Alex. In your experience, what are some of the common errors that law firms make when they are going through some form of digital transformation?

There’s obviously no one thing you can point at. Every project is going to be different, every law firm is unique.

But if I was pushed, I would say that a lot of lawyers underestimate the scale of the undertaking. It’s not just a piece of software you are buying – it’s an investment in the firm’s way of functioning. It’s asking people to buy into new systems and change their behaviours in return for an improved experience.

And they sometimes don’t appreciate that is needs to be treated as an IT project that needs to be methodically managed. It is not a purchase from a vendor, whose salesperson says the right things when the firm is looking to make a change.

The problem with that approach is that they miss out the important groundwork. They don’t do the hard work to understand what the firm actually needs. It’s naturally much more interesting to go straight to the market and go shopping.

The end result is shoe-horning an expensive piece of software into a practice. It’s unlikely to do everything the firm needs it to (because nobody bothered to find out what that was) and people aren’t going to engage in making it work properly. If that happens, everyone involved ends up frustrated and will think twice about future projects.

So when you’re working with a firm, how do you change that approach?

By doing the opposite!

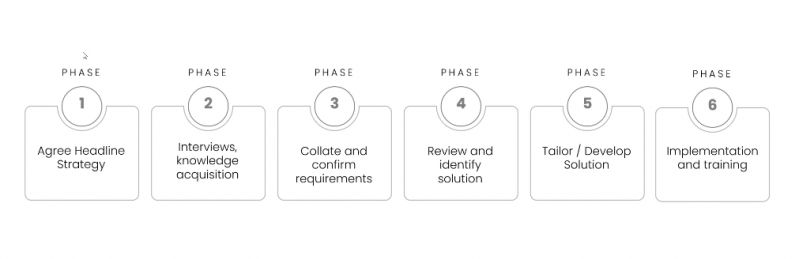

Without revealing the secret sauce, I always approach law firm IT projects with the same basic methodology I developed over the years to minimise risk. The framework is based on the principles of change management in the IT sector.

It’s nothing revolutionary, but it is a nice logical way to get all the building blocks in place before committing to a purchase and implementation.

Go on then, what does this approach involve?

Well, it’s less complicated than it might look on paper!

First, we agree on the headline strategy and the business case for making fundamental changes. This is more than just change for change sake. We need to be able to articulate the problem we are trying to address, or the opportunity that we are trying to exploit.

This first step is very important and it shouldn’t be rushed. It is the project’s guiding light. Very often, we need to remind ourselves of the headline strategy when the project gets difficult. Otherwise, it will be at risk of being abandoned.

Then secondly, we do the work of properly understanding how the firm currently works – often called knowledge acquisition. We are looking for a deep analysis of what works well, what makes it work well and why it needs to be retained. Also, where the pain points are and why they are such a problem.

This allows us to move on to drawing together a project brief, meaning we can articulate what the firm’s requirements are. This isn’t a broad aspirational goal. It is a list of features and benefits that the new system needs to bring.

At this point, the senior management team will need to be involved to either approve the project (and allocate a budget) or abandon the project due to cost, practicality or minimal gains. Sticking with what you know (warts and all) is often the lowest risk strategy. At least the firm will avoid the pain of buying and implementing an unsuitable system. A good IT project manager will be able to identify if ‘do nothing’ is a viable option.

Assuming the project is given the green light, we can then identify potential vendors who meet our requirements. We can very quickly identify those systems that are not suitable, and those that potentially are. It’s this stage that many law firms jump into straightaway, which opens the project up to being entirely led by the vendors.

Once we have chosen a solution (which might actually be a self-developed application), then there is a stage where we tailor the system to the firm’s needs. This avoids a system being a completely ‘out of the box’ generic set up, which doesn’t account for the firm’s way of working. Most vendors are pretty good at this, so long as they know how the product needs to be customised. Again, the knowledge acquisition stage comes into play here.

Finally comes the implementation phase, which is a big piece of work in its own right. There will be technical risks that have to be dealt with (such as data loss or business interruption) and teething problems need to be identified quickly and addressed.

The human users are perhaps the most unpredictable variable in all the project, but if we have done the work of going through the process, it should be an easier sell, rather than “here you go, use this new system”. People need to buy into the logic of the system before they are willing to engage with it. The last thing you want is for people to start looking for ways to circumvent a system because they don’t see the benefit, or find it too cumbersome.

So IT projects have implications for compliance and risk management?

Yes, that’s right. A poorly managed IT project could leave a firm vulnerable in lots of ways. Failure to understand what is needed, not having the best tools for the job, or not implementing new systems properly could leave the firm exposed to IT security risks, financial risks and culture risks. All of which have an impact on reputation in the market.

I usually suggest that the firm’s compliance people are involved in IT projects. They will have input into what new systems need to be able to do, and they can keep the risk of IT failure on the radar during the implementation phase. There is always a chance that something could go wrong when new systems go live, and we need to minimise that risk. If I were a COLP I would keep all current IT projects on the risk register, regardless of size.